The Science Behind Hunger and Satiety Signals

Published January 2026

How Your Body Communicates Nutritional Needs

Hunger and satiety are not simple sensations. They are the result of complex communication systems involving multiple hormones, neural pathways, and environmental cues working together to signal your body's nutritional needs.

Understanding these signals can help you recognise what your body is communicating, though it's important to note that the interpretation of these signals varies significantly between individuals.

Key Hormones in Appetite Regulation

Several hormones play important roles in regulating appetite and feeding behaviour:

Ghrelin

Often called the "hunger hormone," ghrelin is produced primarily in the stomach. Levels of ghrelin increase when your stomach is empty and decrease after eating. However, ghrelin levels are influenced by many factors including sleep patterns, stress levels, and regular eating schedules.

Leptin

Leptin is produced by fat cells and communicates to the brain about the body's energy stores. It generally promotes feelings of fullness. However, leptin resistance—where the brain doesn't respond appropriately to leptin signals—can occur in certain conditions.

Peptide YY (PYY)

Released by intestinal cells after eating, PYY contributes to feelings of satiety and fullness. Levels increase as food moves through the digestive system.

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1)

Released in response to food intake, GLP-1 slows gastric emptying and promotes satiety. It plays an important role in blood sugar regulation and appetite control.

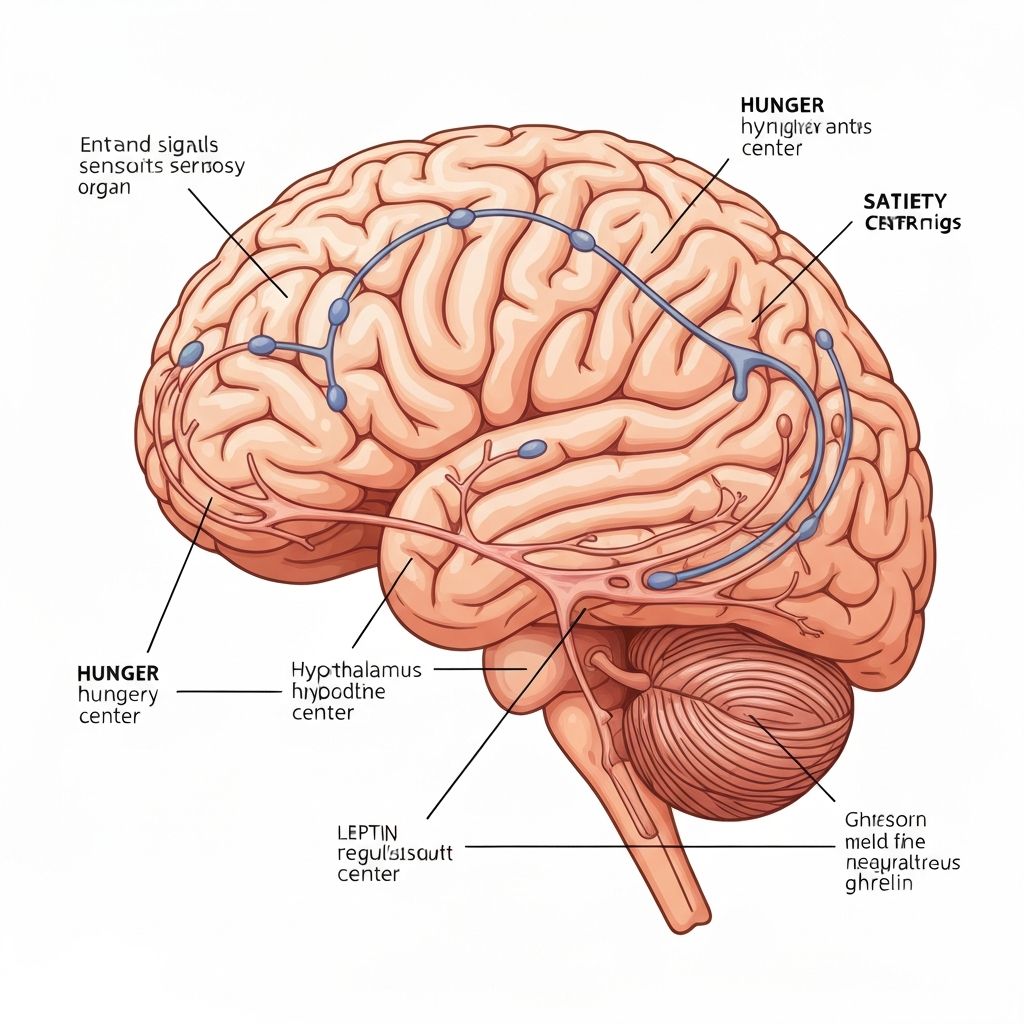

Beyond Hormones: Neurological Signals

While hormones are important, the nervous system also plays a crucial role in hunger and satiety. The brain integrates multiple types of information:

- Gastric distension: Stretch receptors in the stomach signal fullness based on the volume of food consumed

- Nutrient sensing: The intestines detect different macronutrients and send signals accordingly

- Temperature regulation: Eating can affect core body temperature, which influences satiety

- Blood glucose: Changes in blood sugar levels are monitored and influence hunger signals

Factors Influencing Hunger and Satiety

Many factors beyond simple biological need influence how strong hunger signals feel and how readily satiety is recognised:

Sleep and Rest

Sleep deprivation affects ghrelin and leptin levels, typically increasing hunger signals and reducing satiety recognition. This is one reason inadequate sleep is associated with changes in eating patterns.

Stress and Cortisol

Chronic stress affects appetite hormones and can increase cravings for certain foods. Cortisol, released during stress, influences food preferences and eating patterns.

Physical Activity

Exercise affects appetite hormones and can temporarily suppress hunger signals, though the effects vary between individuals and types of activity.

Regular Meal Timing

Eating on a regular schedule helps synchronise hunger signals with meal times. Irregular eating patterns can lead to misaligned hunger and satiety signals.

Macronutrient Composition

Different nutrients have different effects on satiety. Protein generally promotes stronger satiety signals than simple carbohydrates, though individual responses vary.

Individual Variation

It's important to recognise that the strength and clarity of hunger and satiety signals varies greatly between individuals. Factors contributing to this variation include:

- Genetics and inherited metabolic differences

- Body composition and metabolic rate

- Medications and health conditions

- History of dieting and eating patterns

- Psychological and emotional factors

- Environmental and cultural influences

Recognising Your Own Signals

Because hunger and satiety are complex and individually variable, learning to recognise your own patterns can be helpful. This might involve noticing:

- When you typically experience hunger signals

- What physical sensations accompany true hunger versus other eating triggers

- How quickly you feel satisfied after eating

- How different foods or situations affect your appetite signals

This is observational awareness rather than judgment—simply noticing patterns without evaluating them as good or bad.

A Note on This Information

This article explains the scientific basis of hunger and satiety. However, how these signals function in any individual is highly variable and depends on many personal factors. If you have concerns about appetite, satiety, or eating patterns, consulting with healthcare professionals who understand your individual situation is important.